Jupiter

(Jupiter: The Big giant,internal Structure, Atmosphere,Red spots,Planetary rings,Moons)

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a giant planet with a mass one-thousandth that of the Sun, but two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined. Jupiter and Saturn are gas giants; the other two giant planets, Uranus and Neptune are ice giants. Jupiter has been known to astronomers since antiquity. The Romans named it after their god Jupiter. When viewed from Earth, Jupiter can reach an apparent magnitude of −2.94, bright enough for its reflected light to cast shadows, and making it on average the third-brightest object in the night sky after the Moon and Venus.

Jupiter is primarily composed of hydrogen with a quarter of its mass being helium, though helium comprises only about a tenth of the number of molecules. It may also have a rocky core of heavier elements, but like the other giant planets, Jupiter lacks a well-defined solid surface. Because of its rapid rotation, the planet's shape is that of an oblate spheroid (it has a slight but noticeable bulge around the equator). The outer atmosphere is visibly segregated into several bands at different latitudes, resulting in turbulence and storms along their interacting boundaries. A prominent result is the Great Red Spot, a giant storm that is known to have existed since at least the 17th century when it was first seen by telescope. Surrounding Jupiter is a faint planetary ring system and a powerful magnetosphere. Jupiter has at least 69 moons, including the four large Galilean moons discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Ganymede, the largest of these, has a diameter greater than that of the planet Mercury.

Jupiter has been explored on several occasions by robotic spacecraft, most notably during the early Pioneer and Voyager flyby missions and later by the Galileo orbiter. In late February 2007, Jupiter was visited by the New Horizons probe, which used Jupiter's gravity to increase its speed and bend its trajectory en route to Pluto. The latest probe to visit the planet is Juno, which entered into orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Future targets for exploration in the Jupiter system include the probable ice-covered liquid ocean of its moon Europa.

Internal structure

Jupiter is thought to consist of a dense core with a mixture of elements, a surrounding layer of liquid metallic hydrogen with some helium, and an outer layer predominantly of molecular hydrogen. Beyond this basic outline, there is still considerable uncertainty. The core is often described as rocky, but its detailed composition is unknown, as are the properties of materials at the temperatures and pressures of those depths (see below). In 1997, the existence of the core was suggested by gravitational measurements, indicating a mass of from 12 to 45 times that of Earth, or roughly 4%–14% of the total mass of Jupiter. The presence of a core during at least part of Jupiter's history is suggested by models of planetary formation that require the formation of a rocky or icy core massive enough to collect its bulk of hydrogen and helium from the protosolar nebula. Assuming it did exist, it may have shrunk as convection currents of hot liquid metallic hydrogen mixed with the molten core and carried its contents to higher levels in the planetary interior. A core may now be entirely absent, as gravitational measurements are not yet precise enough to rule that possibility out entirely.

The uncertainty of the models is tied to the error margin in hitherto measured parameters: one of the rotational coefficients (J6) used to describe the planet's gravitational moment, Jupiter's equatorial radius, and its temperature at 1 bar pressure. The Juno mission, which arrived in July 2016, is expected to further constrain the values of these parameters for better models of the core.

The core region may be surrounded by dense metallic hydrogen, which extends outward to about 78% of the radius of the planet. Rain-like droplets of helium and neon precipitate downward through this layer, depleting the abundance of these elements in the upper atmosphere.

Above the layer of metallic hydrogen lies a transparent interior atmosphere of hydrogen. At this depth, the pressure and temperature are above hydrogen's critical pressure of 1.2858 MPa and critical temperature of only 32.938 K. In this state, there are no distinct liquid and gas phases—hydrogen is said to be in a supercritical fluid state. It is convenient to treat hydrogen as gas in the upper layer extending downward from the cloud layer to a depth of about 1,000 km, and as liquid in deeper layers. Physically, there is no clear boundary—the gas smoothly becomes hotter and denser as one descends.

The temperature and pressure inside Jupiter increase steadily toward the core, due to the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism. At the pressure level of 10 bars (1 MPa), the temperature is around 340 K (67 °C; 152 °F). At the phase transition region where hydrogen—heated beyond its critical point—becomes metallic, it is calculated the temperature is 10,000 K (9,700 °C; 17,500 °F) and the pressure is 200 GPa. The temperature at the core boundary is estimated to be 36,000 K (35,700 °C; 64,300 °F) and the interior pressure is roughly 3,000–4,500 GPa.

Atmosphere

Jupiter has the largest planetary atmosphere in the Solar System, spanning over 5,000 km (3,000 mi) in altitude. Because Jupiter has no surface, the base of its atmosphere is usually considered to be the point at which atmospheric pressure is equal to 100 kPa (1.0 bar).

Jupiter has the largest planetary atmosphere in the Solar System, spanning over 5,000 km (3,000 mi) in altitude. Because Jupiter has no surface, the base of its atmosphere is usually considered to be the point at which atmospheric pressure is equal to 100 kPa (1.0 bar).Cloud layers

The movement of Jupiter's counter-rotating cloud bands. This looping animation maps the planet's exterior onto a cylindrical projection.

Jupiter is perpetually covered with clouds composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. The clouds are located in the tropopause and are arranged into bands of different latitudes, known as tropical regions. These are sub-divided into lighter-hued zones and darker belts. The interactions of these conflicting circulation patterns cause storms and turbulence. Wind speeds of 100 m/s (360 km/h) are common in zonal jets. The zones have been observed to vary in width, color and intensity from year to year, but they have remained sufficiently stable for scientists to give them identifying designations.

The cloud layer is only about 50 km (31 mi) deep, and consists of at least two decks of clouds: a thick lower deck and a thin clearer region. There may also be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia layer. Supporting the idea of water clouds are the flashes of lightning detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter. These electrical discharges can be up to a thousand times as powerful as lightning on Earth. The water clouds are assumed to generate thunderstorms in the same way as terrestrial thunderstorms, driven by the heat rising from the interior.

The orange and brown coloration in the clouds of Jupiter are caused by upwelling compounds that change color when they are exposed to ultraviolet light from the Sun. The exact makeup remains uncertain, but the substances are thought to be phosphorus, sulfur or possibly hydrocarbons. These colorful compounds, known as chromophores, mix with the warmer, lower deck of clouds. The zones are formed when rising convection cells form crystallizing ammonia that masks out these lower clouds from view.

Jupiter's low axial tilt means that the poles constantly receive less solar radiation than at the planet's equatorial region. Convection within the interior of the planet transports more energy to the poles, balancing out the temperatures at the cloud layer.

Great Red Spot and other vortices

Time-lapse sequence from the approach of Voyager 1, showing the motion of atmospheric bands and circulation of the Great Red Spot. Recorded over 32 days with one photograph taken every 10 hours (once per Jovian day). See full size video.

Time-lapse sequence from the approach of Voyager 1, showing the motion of atmospheric bands and circulation of the Great Red Spot. Recorded over 32 days with one photograph taken every 10 hours (once per Jovian day). See full size video.The best known feature of Jupiter is the Great Red Spot, a persistent anticyclonic storm that is larger than Earth, located 22° south of the equator. It is known to have been in existence since at least 1831, and possibly since 1665. Images by the Hubble Space Telescope have shown as many as two "red spots" adjacent to the Great Red Spot. The storm is large enough to be visible through Earth-based telescopes with an aperture of 12 cm or larger. The oval object rotates counterclockwise, with a period of about six days. The maximum altitude of this storm is about 8 km (5 mi) above the surrounding cloudtops.

The Great Red Spot is large enough to accommodate Earth within its boundaries. Mathematical models suggest that the storm is stable and may be a permanent feature of the planet. However, it has significantly decreased in size since its discovery. Initial observations in the late 1800s showed it to be approximately 41,000 km (25,500 mi) across. By the time of the Voyager flybys in 1979, the storm had a length of 23,300 km (14,500 mi) and a width of approximately 13,000 km (8,000 mi). Hubble observations in 1995 showed it had decreased in size again to 20,950 km (13,020 mi), and observations in 2009 showed the size to be 17,910 km (11,130 mi). As of 2015, the storm was measured at approximately 16,500 by 10,940 km (10,250 by 6,800 mi), and is decreasing in length by about 930 km (580 mi) per year.

Storms such as this are common within the turbulent atmospheres of giant planets. Jupiter also has white ovals and brown ovals, which are lesser unnamed storms. White ovals tend to consist of relatively cool clouds within the upper atmosphere. Brown ovals are warmer and located within the "normal cloud layer". Such storms can last as little as a few hours or stretch on for centuries.

Even before Voyager proved that the feature was a storm, there was strong evidence that the spot could not be associated with any deeper feature on the planet's surface, as the Spot rotates differentially with respect to the rest of the atmosphere, sometimes faster and sometimes more slowly.

In 2000, an atmospheric feature formed in the southern hemisphere that is similar in appearance to the Great Red Spot, but smaller. This was created when several smaller, white oval-shaped storms merged to form a single feature—these three smaller white ovals were first observed in 1938. The merged feature was named Oval BA, and has been nicknamed Red Spot Junior. It has since increased in intensity and changed color from white to red.

In April 2017, scientists reported the discovery of a "Great Cold Spot" in Jupiter's thermosphere at its north pole that is 24,000 km (15,000 mi) across, 12,000 km (7,500 mi) wide, and 200 °C (360 °F) cooler than surrounding material. The feature was discovered by researchers at the Very Large Telescope in Chile, who then searched archived data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility between 1995 and 2000. They found that, while the Spot changes size, shape and intensity over the short term, it has maintained its general position in the atmosphere across more than 15 years of available data. Scientists believe the Spot is a giant vortex similar to the Great Red Spot and also appears to be quasi-stable like the vortices in Earth's thermosphere. Interactions between charged particles generated from Io and the planet's strong magnetic field likely resulted in redistribution of heat flow, forming the Spot.

Moons

Jupiter has 69 known natural satellites. Of these, 53 are less than 10 kilometres in diameter and have only been discovered since 1975. The four largest moons, visible from Earth with binoculars on a clear night, known as the "Galilean moons", are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

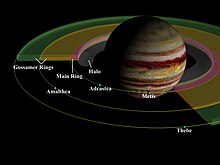

Planetary rings

Jupiter has a faint planetary ring system composed of three main segments: an inner torus of particles known as the halo, a relatively bright main ring, and an outer gossamer ring. These rings appear to be made of dust, rather than ice as with Saturn's rings. The main ring is probably made of material ejected from the satellites Adrastea and Metis. Material that would normally fall back to the moon is pulled into Jupiter because of its strong gravitational influence. The orbit of the material veers towards Jupiter and new material is added by additional impacts. In a similar way, the moons Thebe and Amalthea probably produce the two distinct components of the dusty gossamer ring. There is also evidence of a rocky ring strung along Amalthea's orbit which may consist of collisional debris from that moon.

Jupiter has a faint planetary ring system composed of three main segments: an inner torus of particles known as the halo, a relatively bright main ring, and an outer gossamer ring. These rings appear to be made of dust, rather than ice as with Saturn's rings. The main ring is probably made of material ejected from the satellites Adrastea and Metis. Material that would normally fall back to the moon is pulled into Jupiter because of its strong gravitational influence. The orbit of the material veers towards Jupiter and new material is added by additional impacts. In a similar way, the moons Thebe and Amalthea probably produce the two distinct components of the dusty gossamer ring. There is also evidence of a rocky ring strung along Amalthea's orbit which may consist of collisional debris from that moon.

No comments:

Post a Comment